A Movie Like The Matrix Might Never Happen Again

On its 20th anniversary, the sci-fi classic is as dazzlingly original as ever—too much so for the risk-averse Hollywood of today.

A recent video from Will Smith confirmed a long-standing piece of Hollywood trivia: He was the first choice to play Neo, the lead role in the Wachowskis’ The Matrix, but he turned it down. The decision was one he says he’s “not proud of,” but his reasoning was simple—he didn’t understand the pitch he had received from the filmmakers at all. “Imagine you’re in a fight,” Smith recalls the sibling director duo telling him during a meeting. “And then you, like, jump—and imagine if you could stop jumping in the middle of the jump.” Smith might be exaggerating for comedy’s sake, but the thrust of his explanation for rejecting the part makes sense. Which prompts a question: In a risk-averse business like Hollywood, how did a movie like The Matrix—demanding in terms of both concept and cost—get made in the first place?

The film came out exactly 20 years ago, before 1999’s summer action-movie season had even begun; The Matrix’s big competitors at the theater were comedies such as 10 Things I Hate About You and Analyze This. As an R-rated sci-fi epic about hackers who know kung fu and do battle with machines in a postapocalyptic wasteland, The Matrix was difficult to describe. Yet it somehow became a word-of-mouth hit, the rare blockbuster that opens at No. 1 at the box office, falls to No. 2, and then climbs back to the top position (which it did in its fourth week). It’s the kind of dazzling, original film that inspires a generation of fans and imitators—and the kind of movie Hollywood wouldn’t make in today’s franchise-heavy media landscape.

Ironically, viewers will probably get a hackneyed attempt at a Matrix revival (Warner Bros. has reportedly been mulling one for years) before they get a major-studio project that approaches the original’s ingenuity. The Matrix was a mash-up of Lana and Lilly Wachowski’s many interests, blending their love of anime, martial-arts movies, cyberpunk literature, electronic music, and post-structuralist philosophy into a mainstream action flick. The directors, still relatively unknown at the time, managed to do all of that on a moderate budget of $63 million, leaning on perfectly pre-visualized action sequences that helped define the next decade of cinema.

Twenty years on, much is being written about 1999 as a crucial turning point for Hollywood. By the end of the 20th century, the industry was suddenly crowded with directors fresh from making indie cinema, buzzy music videos, and commercials, many of whom had grown up with the rebellious New Hollywood filmmakers of the ’70s as their artistic lodestars. The future of moviemaking was foreshadowed in the year’s big hits, which included the relaunched big-ticket franchise Star Wars (The Phantom Menace), the low-budget horror of The Blair Witch Project, the provocative teen humor of American Pie, and the twist-ending virality of The Sixth Sense.

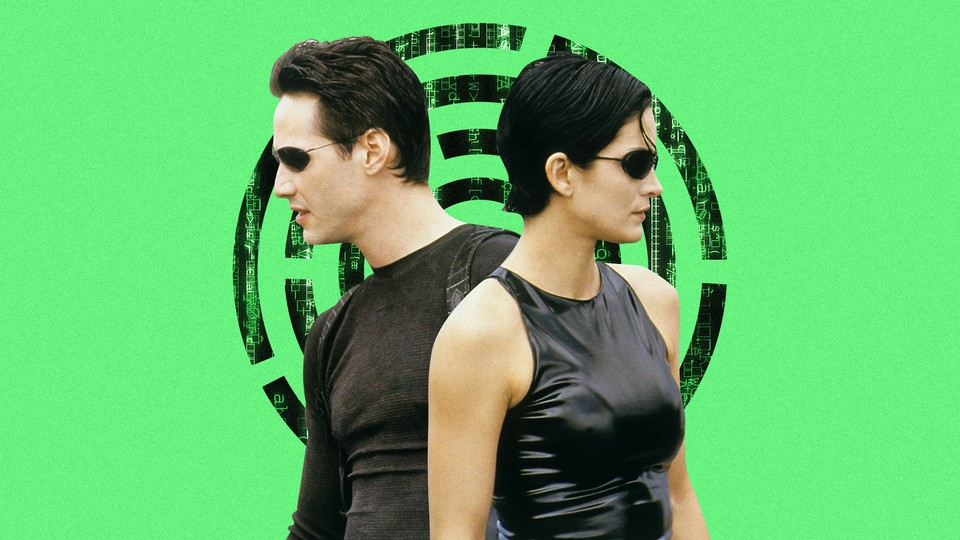

Though bits and pieces of The Matrix have been copied over the years—the slow-motion action dubbed “bullet time,” the leather outfits—the film’s DNA is impossible to transpose. With its narrative of a world where the wool has been pulled over everyone’s eyes, it feels like a movie that’s very much about the disillusionment that comes at the end of a century. Neo (Keanu Reeves) is a hacker who learns that reality is a mere computer program designed to keep humans in line as machines siphon away their body heat for energy. The Matrix is a triumph of screenwriting in that it conveys all its convoluted plot machinations with ease, dramatizing long-winded explanations by setting them against electrifying imagery.

After freeing his mind, Neo becomes a superhero of sorts, able to bend the rules of physics, jump across buildings, learn any skill, and fight any bad guy. But what’s most appealing about Neo is his openness, and the way Reeves (one of the premier pretty boys of the ’90s) can convey both bafflement and braggadocio in a line like “I know kung fu.” Reeves understood that Neo needed to be more than a plug-and-play hero, and the character’s guilelessness grounds the audience amid all the heady world building.

Watching today, Neo seems like the poster boy for a disaffected Generation X, a nonconformist who escapes his dull life as a cubicle drone to become a god. (In fact, one of The Matrix’s closest thematic companions from the fertile cinema du 1999 is probably Mike Judge’s Office Space—another sad ballad about humans being swallowed whole by faceless corporations, though Judge’s film has a few more jokes.) The villains of The Matrix are invincible computer programs known as Agents, led by the stone-faced Smith (Hugo Weaving), that take on the appearance of anonymous-looking government officials in bland suits and ties. Meanwhile, Neo and his compatriots, including Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne) and Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss), dress like they’re attending a fetish club, and they do battle to a thumping soundtrack of heavy metal and techno music.

For many, the thrill of The Matrix ends with The Matrix. Its sequels, The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions, filmed back-to-back and both released in 2003, were financial winners, but the critical responses they received were more mixed. The Wachowskis moved on to other, spectacular but niche properties such as Speed Racer and Cloud Atlas, and have yet to make another hit—though each of their films gained a cult following in the years after its release, making The Matrix’s immediate success feel all the more serendipitous.

Even when building off their biggest hit, the Wachowskis couldn’t resist digging deeper. The first Matrix film sets Neo on a biblical hero’s journey that involves sacrifice, resurrection, and the acquiring of Messiah-like powers. The sequels turn that narrative on its head with the revelation that Neo’s status as “the One” is merely a myth designed by his machine overlords to keep the rebels focused on an impossible goal. That bold gambit sums up the Wachowskis’ commitment to inventive storytelling and challenging audiences at every turn. Viewers are lucky they chose to challenge Hollywood as well.